Monday, June 21, 1915

Reserve Billets, Le Quesnoy

The Battalion War Diarist wrote nothing for this day: [1]

THIS DAY IN RMR HISTORY: “British Headquarters, France, June 21. – “How are the turrets? Still holding out?” they ask up and down the line of anyone who has come from Ypres. Everybody has a tender personal interest in the turrets of the old Cloth Hall, which deepens with each day that they survive in defiance of the German gunners above the wreckage wrought by German shells.

People are still living in Rheims and Louvain, but Ypres is absolutely a dead city; dead as Pompeii; dead as a deserted mining camp in Alaska. No face appears in any door or window that can still be called a door or window; no figures are seen moving through the shell holes in walls that are still standing.

City is deserted: Before the war Ypres had some 18,000 inhabitants. Now it has not a single one. No one is making any effort to make any ruins habitable. The only signs of life except occasional soldiers coming out and going to the lines are cats grown wild which become streaks of fur disappearing among the ruins of their former homes.

City is deserted: Before the war Ypres had some 18,000 inhabitants. Now it has not a single one. No one is making any effort to make any ruins habitable. The only signs of life except occasional soldiers coming out and going to the lines are cats grown wild which become streaks of fur disappearing among the ruins of their former homes.

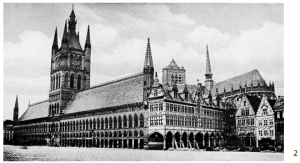

The cathedral, which stands back of the Cloth Hall, was a noble edifice no doubt, but there are a great many cathedrals in Europe. The Cloth Hall is unique; the best of its kind. Anyone who ever saw it always remembered its turrets. Different conquerors of Ypres put their women and children to the sword, but no one had ever harmed the old Cloth Hall beyond taking away a few statues.

Last February perhaps 4000 or 5000 people remained in Ypres. They were going and coming about the streets as usual, keeping their shops open and doing what business they could at the old stand. A visitor could get a meal in a restaurant or have his shoes cobbled. Only one house in the big square had been hit. Its roof dropped over the edges of a corner section which had been torn out of the main floor.

Cloth Hall Recently Restored: The Germans threw in occasional shells, mostly directed at the cathedral, with some of the missiles bound to hit the Cloth Hall. Restoration work which age required had just been finished on the Cloth Hall before the war began. The people paid for this in their civic pride and let other civic improvements wait. For the Cloth Hall gave to Ypres a civic distinction. It was the historical soul of Ypres. The old frescoes on its walls told the city’s early history. It meant to Ypres quite as much in its way as Westminster Abbey to London or Fanueil Hall to Boston. Every man or woman born in Ypres had been brought up to tell the time of day by the raised gilt figures of the old golden clock face.

By February the people’s sense of horror was exhausted. Destruction of things sacred to them had become routine. When they heard another explosion and word was passed that the Germans had scored another hit they went around to the Grande Place to see if the turrets and the gilt clock face were still unharmed. And they said ‘The Cloth Hall can still be restored.’ – These stubborn Flemish who would not let shell fire drive them away from their old town.

Smashed in Second Attack: The next time the Associated Press correspondent went to Ypres there was not a single house left on the Grande Place that resembled a house any more than a rubber bag with the gas out of it resembles a balloon. In the second battle of Ypres, when the Germans had another try for the channel ports, the sensation of their attack with asphyxiating gas overshadowed what they did with their guns. Heretofore their practice on Ypres had been comparatively teasing playfulness. This time they went at the job of destruction systematically; jumping from one space on the checkerboard to another, they smashed Ypres section by section.

As they meant to take the town this seemed poor policy, for they would find no roofs for shelter when they moved in. But their object was confusion for the British reinforcements hurrying up along roads crowded with refugees, wholesale death for men in billets in town, and destruction and delay for supplies and munitions coming through the streets. This was excellent theory, which did not work out in practice. The British were not billeting troops to any extent in Ypres, and you could count the number of army wagons hit on the fingers of one hand. One shell in the British trenches accomplished more than ten in Ypres. The main result was that the homes and offices and cafes of 18,000 people were destroyed.

Shells Spread Ruin: The 42 centimeter (17 inch) mortar had its part in the work. When a 17 inch shell struck a house the remains of the building not distributed on the pavement were in an enlarged cellar. Debris in the streets still remains where it fell. There is no purpose in cleaning it up in an uninhabited town. Paving stones are scattered about from the explosion of a 17 inch shell which struck in the center of the Grande Place and made a crater about 15 feet across and 10 feet deep.

This 2000 pounds of steel and powder did not kill anybody so far as could be learned. It would not take a paving gang long to make repairs. Another shell which could have brought down a cathedral tower dug a still larger crater in the soft earth of the cathedral grounds. Big shells or little shells, they do not count unless they hit. On the principle that lightning never strikes twice in the same place, probably the safest cover one could find in case of another bombardment of Ypres would be to sit in the bottom of one of those craters.

Waste of Powder: Another bombardment would seem as bootless as flailing last year’s straw or kicking a dead dog. However, the Germans keep on throwing shells into the wreckage at intervals as if they could never be satisfied that they had properly finished the job of chaos. Every standing wall was chipped with shrapnel. If there was a house which looked from the outside as if it were unhit it would be found that it had been eviscerated by a shell through the roof.

‘Well, what do you think of Ypres, as a place of residence?’ asked an officer who rode by.

‘Pretty rotten,’ the visiting correspondent replied.

‘I know one that is rottener,’ he replied with a suggestive nod back towards the trench line beyond Ypres.

‘Were the turrets still holding out?’ The visitors could report that they were. To the German gunners they must be like the high apple on the tree that will not come down for the small boys’ stone throwing.

Cost is Enormous: It must have cost about $200,000 in shells to destroy Ypres by manufactured piecemeal earthquake and it will cost several millions to restore it.

Occasionally a father of a family who had to leave the town during the bombardment is able to secure a cart and permission to return to the salvage of the remains of his house. He finds that nothing has been disturbed except by shell fire. Ypres is forbidden land, where no one may go except on military business. In a sense it is policed, too, in the same way as a rattlesnake’s nest. The citizen who goes to glean a mattress, a bureau and the family Bible from the debris of his roof takes time to see if the turrets and the clock face of the old Cloth Hall are still holding out.” [5]

[1] War Diary, 14th Canadian Battalion, The Royal Montreal Regiment, June 21, 1915. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa http://data2.collectionscanada.ca/e/e044/e001089753.jpg

[2] http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/18/Collier's_1921_World_War_-_Cloth_Hall_of_Ypres.jpg

[3] http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_Rt6v5QrkZew/S98VTWAqgsI/AAAAAAAAAKc/-WzJPl6hGug/s1600/Ypres_in_Ruins.gif

[4] “Not A Human Soul In Ypres,” The Day, New London, Connecticut, Thursday, July 8, 1915, pg. 3, col. 3.

[5] Ibid