By Buzz Bourdon (late the RMR, 1975-82)

When the Royal Montreal Regiment resumed training in Montreal after the Second World War, its officers and soldiers wore exactly the same uniforms and equipment the overseas battalion had worn. The army had enormous stocks of uniforms, webbing and accoutrements on hand so it certainly wasn’t in a hurry to start procuring anything new.

The basic working uniform for the troops was the two-piece khaki uniform officially known as battledress, serge. It was first adopted by the British army in 1939, just before the start of the war. The short jacket, or blouse, of wool serge, buttoned to the outside of high-waisted wool serge trousers.

The blouse featured a closed collar secured by two hooks and eyes, and buttons down the front. There were two large breast pockets. NCOs – lance corporals, corporals, sergeants and staff sergeants wore their badges of rank on both sleeves, above the elbow. Warrant officers, both class one and class two, wore theirs about five inches from the bottom of their sleeves. Undress medal ribbons were worn above the left breast pocket. The khaki coloured RMR shoulder flash, both canvas and cloth, was worn at the top of both sleeves, the top edge touching the shoulder seam. Skill at arms badges were worn on the bottom of the left sleeve, as were wound stripes and the small chevrons denoting years served overseas. To indicate rank, the officers wore the usual cloth Tudor crowns and stars, or pips, on the shoulder straps.

Wikipedia has this to say about the trousers: “On the trousers, there was a large map pocket on the front near the left knee and a special pocket for a field dressing near the right front pocket (on the upper hip). The mixed green and brown fibres of the British battledress fabric matched the colours of heath and forests of the United Kingdom fairly well without having to be a single muddy olive green colour like American uniforms. The gap between the blouse and trousers would open up in extreme movement and buttons popped, so braces (suspenders) were issued.

“When the trousers were worn with the cloth puttees, we wore lead weights in the trouser legs to cause the extra length of the leg to “blouse” neatly over the top of the puttee. The weights I had were tubes of cotton stitched into a continuous circlet into which 9mm bullet slugs (perhaps 25 or 30 in each circlet) had been inserted for weight, before the cotton tubing has been stitched closed. These circlets were pulled over the foot and under the trouser cuff before the boot was pulled onto the foot,” said retired Capt Hamilton Slessor, who served in the RMR 1961-66.

Wikipedia adds: “A woolen shirt was typically worn under the wool blouse. An open collar blouse (with tie) was initially restricted to officers, other ranks buttoning the top button of the blouse and closing the collar with a double hook-and-eye arrangement. Short canvas anklets (gaiters) or puttees covered the gap between the trousers and the ankle boots, further adding to the streamlined look and keeping dirt out of the boots without having to use a taller, more expensive leather boot.”

Slessor remembers his shirts as “khaki colour, probably cotton flannel, but later only plain cotton shirt material. In many instances officers’ shirts and ties were of a much lighter colour khaki, (almost tan in some cases) than the darker khaki worn by (the troops).” His father Eric had fought with the RMR, as a subaltern, during the First World War and commanded the unit from 1936-40. When Canada declared war against Germany on Sept. 10, 1939, the elder Slessor mobilized the RMR and took it to Britain. He handed command over to LCol Victor Whitehead in 1940.

In 1943, Canada modified the collar closure of the blouse by changing from a set of hooks and eyes to a flap and button. The Canadian version was also a much greener shade of khaki than the standard British version.[6] It was greenish with some brown, rather than brownish with some green. Buttons were green painted steel, with a central bar across the middle for the thread to hold in place.

By the end of the 1940s a final version of battledress was issued to the army and the RMR. Pattern 1949 had broad lapels added to the blouse, giving it an open-collar design. Now everyone would wear a collar with the shirt, plus a tie, not just the officers. The field dressing pocket was also removed from the trousers after the war.

Although it was designed for combat, battledress could actually look quite smart as a walking-out uniform if pains were taken to make it so. Pressing the trousers and shining the black drill boots worked wonders. The heavy khaki web belt, originally with a very basic and nondescript type of generic metal fastening, was also worn, and senior NCOs of the RMR wore their scarlet worsted infantry sash over the right shoulder. Lance sergeants did not wear the sash.

Officers carried a leather covered swagger stick. Field officers (majors and above) carried sticks that were usually leather covered cane or wood, said Slessor, about three-quarter inch in diameter and about 18-inches long. Subalterns (second lieutenants and lieutenants) often carried thin, three-eighths of an inch in diameter canes with chrome ends. The top end featured either a round ball or a tapered cap, he said.

“Swagger sticks were a nuisance, one would put them down, and then forget where they had been left. Many of my contemporaries in the 1960s did not bother with them,” remembered Slessor.

As for headdress, the officers wore a khaki service dress cap, commonly called the forage cap, complete with a bronze badge, with battledress. They rarely wore the RMR’s postwar scarlet beret, according to Maj James Anderson, who served in the RMR from 1957-64. This beret was standard for the RMR’s other ranks, from private to warrant officer, class two. It featured the RMR brass badge, which featured the Tudor, or King’s, Crown. This crown was changed to the St Edward’s Crown some years after Queen Elizabeth II acceded to the throne on Feb. 6, 1952. The RSM of the RMR usually wore the officers’ forage cap.

But Slessor remembers some of the officers wearing the scarlet beret on winter exercises because it “would fit under the hood of a parka which the forage cap did not.”

An early postwar commanding officer of the RMR, LCol Robert Schwob, who commanded from 1947-51, chose to be photographed wearing the scarlet beret. He won the Military Cross at the battle of the Leopold Canal in 1944. In this particular photo, which is in volume two of the RMR’s regimental history, his beret features the officers’ gold and silver bullion embroidered badge. This badge was first worn in 1943 when the RMR adopted the black beret when it became the 32nd Canadian Recce Regiment (RMR). The RMR’s legendary RSM from the war, WO1 James Mitchell, was photographed wearing the black beret complete with bullion badge.

An olive drab cap that looked a lot like a baseball cap – it had a more square shape – was also worn during the early post-war era, sometime after 1950, with the summer bush uniform. The brass cap badge featured a red patch behind it, cut to conform to the shape of the badge.

The RMR continued to wear the battledress uniform until 1971, when it was replaced by the olive drab Canadian Forces combat uniform, first issued to the regular army in 1964. However, starting in the late 1960s, many RMR soldiers purchased combats from army surplus stores and wore them in the field, away from the armoury, on weekend exercises.

Retired LCol Harry Hall, who commanded the RMR twice in a long and distinguished career, remembers getting his combat uniform in December, 1970. The October Crisis had just ended a few weeks earlier and he volunteered, along with others, to guard Longue Pointe, the huge army base in east end Montreal, and Camp Bouchard, over the Christmas holidays.

“Most of us bought a set of combats for the field and weekend exercises – combats were allowed for training only in the field, not around the armoury until officially issued (in 1971). Probably fifty percent of the guys wore them,” said Hall.

As for battledress and bush, the RMR had its own clothing stores for those uniforms. “The RQMS, MWO Harold Goldstein, issued me my first uniform in 1969. In 1971 or so clothing stores were centralized at Cote des Neiges armoury and Longue Pointe,” said Hall, who commanded the RMR from 1989 to 1992, and from 1996 to 1999. Afterwards, he was the honorary lieutenant-colonel from 2004 to 2008, and the honorary colonel from 2008 to 2013.

RQMS Goldstein, known affectionately as ‘RQ,’ joined the RMR in 1936 and served overseas with it during the Second World War. Afterwards, he stayed in until the 1960s and later spent almost 30 years as the much respected steward of the Officers’ Mess. He died in 2000.

THE 1951 WEBBING

For training in the field, and in the armoury, the 1951 pattern webbing was worn by the RMR’s soldiers of this era, right to the middle or late 1970s. The waist belt had 42 metal eyelets in it, in vertical rows of three. This allowed the webbing’s various items to be attached anywhere on the belt. A metal canteen, or water bottle, fit into the canteen cup, which then fit into its carrier. That was attached on the rear of the belt, to the right. To the left of the small of the back, was attached the mess tin carrier, which held the two mess tins. The smaller one fit into the bigger one. The knife, fork and spoon, which fit into each other, was usually stored in the mess tin carrier.

On the front of the belt, which was supported by two narrow braces that crossed at the top, in the back, two ammunition pouches were fastened, one on each side of the buckle. They could be filled with ammo magazines. A small pack could be attached to the belt’s braces, on the rear of the webbing, high on the wearer’s shoulders. The large pack was often carried slung over a shoulder.

There was also a gas mask and an entrenching tool. For wet weather, a large groundsheet could be worn. It featured a hole in the middle, complete with hood, where you stuck your head through. The famous British ‘soup plate’ helmet, worn in combat during two world wars, finished the picture. It was replaced by the American M1 helmet sometime after 1960.

However, this web belt with the rows of metal eyelets was an American pattern, Hamilton Slessor said. “It came to Canada, I would guess, after Korea. It was only worn in the field on exercise in my day (1960s). The web belt worn in the armoury on parade nights for training in the armoury had no holes. It was very heavy webbing with brass keepers and buckle. It was standard Ordnance Corps issue and was worn in the 1950s and 60s with coats of ‘Blanco,’ a liquid paste poured out of a can and wiped onto the canvas and then brushed out until it hardened into a flexible coating and shone.”

By the 1960s, the rectangular brass buckle with the RMR capbadge attached to it was being worn with the heavy khaki belt, as well as the white ceremonial belt worn with patrol dress.

Until the early 1960s, the RMR carried the venerable bolt-action .303 Lee Enfield rifle, as their grandfathers, fathers and uncles had done in both world wars. It was replaced by the modern, high-powered, gas-operated, semi-automatic FN-C1, firing a 7.62 mm round. The automatic C2 version of this weapon used a 30-round magazine and had a folding bi-pod.

Officers rarely carried the Browning 9 mm pistol, said Slessor, “only when drawn from Ordnance stores for special training exercises on the rifle outdoor ranges at Farnham or St. Bruno. I rarely had to requisition pistols ever, while I was the quartermaster in the 1960’s.”

He added, “Because of the FLQ Crisis in Quebec in the late 1960s all weapons were withdrawn from all armouries in the province and had to be requisitioned from RCOC Stores at Longue Pointe on an as needed basis for special parades, or training exercises. For a time whatever was needed (received) had to be stored in armoured vaults installed in the arms room in the basement of the armoury and these had an alarm system wired to the police. On several occasions my parents got a phone call in the middle of the night and I had to attend immediately at the armoury to investigate alarms along with the Commissionaires, then on duty 24/7 in the armoury.”

Eventually the crisis passed and the RMR’s weapons were returned to their proper place in the QM’s weapons vault, where they remain to this day. Properly locked up and secured, of course.

The summer, two-piece bush uniform was worn with the baseball cap, in the early 1950s, at least, or the scarlet beret. Officers usually wore their khaki forage cap. Undress ribbons were worn over the left breast pocket of the shirt and the officers wore slip-ons with cloth stars and pips. NCOs wore their rank sewn on a brassard worn on the right arm. It had the RMR shoulder flash sewn on the top, over the rank. Cloth puttees were worn to secure the bottom of the pants to the tops of the boots. After Mobile Command was established in 1965, its attractive, red, white and blue crest was worn under the RMR flash, on the brassard, and on the sleeves of battledress jackets.

Although the balance of the RMR got its combat uniforms in 1971, the old uniforms were still worn in 1972, Harry Hall said. “Although myself, Vince Colgan, George Donais, Capt Ross Fletcher, had combats as we instructed a SSEP II course in 1972, the troops were issued bush and coveralls. The course was tasked to conduct a Dieppe ceremony in Longueuil on Aug. 19, 1972. Headquarters did a typo and assigned the RMR instead of the FMR. All of us, including the instructors, were in bush for that ceremony. It was a 50-man guard.”

As for coveralls, they were still being worn when Hall joined the RMR, and into the 1970s. “When I did my Infantry Course and Advanced Infantry at Camp Dube, in CFB Valcartier, we wore the coveralls 90% of the time in the field on training – to be frank, that was a good call you could open them up and cool off, easier to clean.”

OFFICERS’ SERVICE DRESS

Although battledress was the everyday working uniform of the RMR during this era, the officers also wore the army’s service dress uniform for certain parades, ceremonies and events, and walking out. This two-piece uniform was comprised of a pair of trousers and a jacket. The jacket had two breast pockets and two larger pockets below the belt. It was purchased from any reputable military outfitter or tailor.

“J.R. Gaunt or William Scully were the usual firms to deal with in Montreal for insignia but the tailoring firm of Samuel Ogulnik were the people from whom we bought our made to measure service dress or blues, as the regiment did not issue these to officers,” said Hamilton Slessor.

The two breast pockets were secured with RMR pattern brass buttons, of 30 ligne. Four 40 ligne buttons were sewn down the front of the jacket to close it. Rank was indicated by the appropriate combination of metal crowns and stars (the Order of the Bath) secured by cotter pins to both shoulder straps. For example, captains wore three stars, or pips, and a major wore a crown. A metal Canada shoulder title was worn on the bottom of each shoulder strap. Undress ribbons were placed over the left breast pocket. Brown shoes were worn and a leather covered swagger stick was carried.

The khaki forage cap complete with the officers’ bronze badge was worn with service dress. The RSM also wore this uniform but his badge of rank was the coloured Royal Arms of Canada, worn about five inches from the bottom of both sleeves.

An important part of the service dress uniform was the leather Sam Browne belt, worn buckled around the waist. The jacket usually had two brass keepers sewn into the waist to keep the belt in position. A leather cross strap was worn diagonally across the right shoulder. It fastened to the belt in two places, to the left of the front buckle and at the back of the belt. The RSM also wore the Sam Browne, which was invented by Gen Sir Sam Browne, VC, of the British army. He had lost his left arm in 1857, during the Indian Mutiny, and thought his invention would help secure his sword to his belt.

Wikipedia says, “Browne came up with the idea of wearing a second belt which went over his right shoulder and held the scabbard in just the spot he wanted. This would hook into a heavy leather belt with ‘D-rings’ for attaching accessories. It also securely carried a pistol in a flap-holster on his right hip and included a binocular case with a neck-strap. Other cavalry officers in the Indian Army began wearing a similar rig and soon it became part of the standard uniform. During the Boer War, the rig was copied by Imperial and Commonwealth troops and eventually became standard issue.”

The Sam Browne belt was supposed to be spitshone to a high polish, usually by the batman, or servant, of each officer, but that was in the regular army. RMR officers did not enjoy the services of a batman after the war.

“The tricky part was to shine the leather but not get Brasso (brass polish) on it, and to shine the brass but not get leather polish on it,” said Slessor.

The officers also wore a red lanyard on the left shoulder of both the service dress jacket and battledress blouse. “Mine had been my father’s so it was obviously worn early (in) WWII and probably well before (perhaps even WWI). The end of the lanyard had a clip on which we wore what seems to be called a ‘Hudson trench whistle,’ which weighed the end of the lanyard in the left breast pocket,” said Slessor.

How much did all these uniforms and accoutrements cost? A lot, by the standards of the day. For example, Montreal’s William Scully Ltd, which billed itself as “The oldest and largest manufacturer in Canada of uniforms and military accoutrements,” stocked everything a newly-minted officer would need. The winter service dress uniform was $90. The Sam Browne belt, complete with electroplated fittings, cost $15.50. A sword was $56.25.

James Anderson, whose three sons served in the RMR after him, for a total of about 33 years for the family of four, remembers paying a lot of money for all his uniforms and accoutrements when he became an officer in 1957. (He had previously served ten years in the Black Watch (RHR) of Canada). There was no clothing allowance, he said. “I remember, as a young officer with a big family, it was expensive.”

He was issued the battledress and bush uniforms from the RMR quartermaster stores but had to go to Scully’s to buy service dress and blue patrols, along with a Sam Browne belt and a swagger stick. “Service dress was not often worn – battledress was the working uniform. Patrol dress was worn for ceremonial parades such as the annual church parade and mess dinners. I would say that 75 percent of the officers did not have mess kit, most wore blue patrols.”

William Scully, which had traded for decades at its landmark store in downtown Montreal, at 1202 University Street, before moving to 50 Craig Street, also stocked the many odds and ends you needed. The RMR’s khaki and blue forage caps were $10 each. The scarlet beret was $3.25. Fox puttees, worn with battledress, were $3.25. Trouser weights were $1.25. A pair of tan ankle boots were $21.50.

Anderson’s scarlet beret, which was made by Grand’mere Knitting Company, Limited, in Grand’mere, PQ, is still in mint condition. That’s because he rarely wore it, he says. It was made in 1952 and the inside liner says it’s a ‘Genuine Basque Beret.’ Size seven and one-eighth.

Other garments were worn at different times of the year. For example, a heavy, double-breasted wool greatcoat was worn during the winter. It featured six, 40 ligne buttons on the front and two shoulder straps. Badges of rank were worn in the usual places, as were RMR shoulder flashes. For field training, a heavy sheepskin coat could be substituted for the greatcoat. A one-piece black coverall was also worn for training in the field, or by recruits who were waiting for their uniforms.

The soldiers of the RMR did not wear service dress during this era. If they weren’t wearing battledress, or bush during the summer, or coveralls, then they were in blue patrols for ceremonial parades and social events.

OFFICERS’ MESS DRESS

This splendid uniform was worn by the officers of the RMR while attending mess dinners, balls and other high-profile events. Over the past 100 years, two versions have been worn, The first version is a short, scarlet jacket that ends at the wearer’s waist. It has a two-inch high collar, with gold braid at the top, that attaches at the front by two hooks and eyes, or a long, vertical bar that fit into a clasp. On either side of the collar is a gilt and silver collar badge – a miniature version of the capbadge – made either by William Scully Ltd or JR Gaunt & Son. Rank was displayed on the shoulder straps by miniature silver and gold embroidered stars and crowns. Metal versions have also been seen.

Instead of the front of the mess kit jacket being secured by buttons, both sides fell away at an angle to the waist. Underneath, the officer wore a navy blue waistcoat that covered the entire chest and stomach, plus a blue cummerbund. A white waistcoat has also been seen. Tight blue overalls with a quarter-inch scarlet stripe on the sides were also worn. The overalls usually featured leather or elastic straps worn under the feet. The overall picture was completed with highly-polished quarter Wellington boots. Field officers and above were supposed to wear spurs with them.

But not all field officers chose to wear spurs, said Slessor. “They were very hazardous when descending a flight of stairs, or on a dance floor!!”

The second version of the RMR mess kit featured a scarlet jacket with shawl collars, like a civilian dinner jacket. This was the style originally worn in the 1930s, according to Slessor. A gilt and silver collar badge was worn on each collar ($5.50 per pair from Scully’s). Worn with a white shirt and black bow tie, a blue waist coat was also worn. Four RMR 20-ligne brass buttons fastened the waistcoat at the bottom. The usual trousers and Wellington boots were worn.

Scully’s mess kit jacket and vest cost $85 (the patrol dress trousers could be worn with this). Miniature medals that paid tribute to the wearer’s service and gallantry in combat were worn on the upper left breast of either jacket. Some wore their miniatures court mounted, some wore them loose.

THE BLUE PATROL UNIFORM

By the middle of the 1950s, the Canadian army was starting to move away from its drab, utilitarian, war-time look. An important part of this official desire to appear more colourful in peace time was the decision to introduce the blue patrol uniform.

In fact, the RMR was apparently the first unit in either the regular army or the militia “to be totally outfitted with Blue walking-out uniforms, with Scarlet berets,” according to the regimental newsletter, the R.M.R. Intercom. In October, 1954, the Intercom was thrilled to announce the news on its front page: “Dress Uniform for all Ranks,” crowed the headline. There was a lot more to read on the topic in the second number of this publication, which originally appeared during the war.

The happy news had been announced to the troops at the first parade of the new training year, in early September, 1954, by the commanding officer, LCol CJ Pratt. “All men will be able to wear the smart blue uniforms for ceremonial parades, dances, parties and social events in the Unit,” the Intercom said.

But recruits would have to wait approximately six months before receiving it, “during which time they will be expected to show that they are worthy of it.” According to the Intercom, The new uniforms were supplied “…from the Regiment with funds that are being specially raised for this purpose,” not from the army and the taxpayer.

This subtle but elegant two-piece uniform was comprised of a smart-looking blue jacket with a two-inch high collar, which was fastened by two hooks and eyes. Five 30-ligne RMR brass buttons closed the garment on the front. There were two breast pockets and two larger pockets below the waist. NCO ranks, made of gold thread, were worn on the right arm above the elbow by lance corporals, corporals, sergeants and staff sergeants. The RSM and the warrant officers, class two, wore their badge of rank above the bottom of the right sleeve. The RMR usually had five or six WO2s during the 1950s.

For example, when WO1 James Mitchell had a group portrait taken of the Warrant Officers and Sergeants’ Mess in 1948, there were seven WO2s sitting on either side of him, in the front row. That picture had 44 senior NCOs in it, plus the commanding officer, LCol Schwob, his deputy, Maj JPC Macpherson and the adjutant, a captain. At least 17 men wore ribbons denoting service in the second war. One man wore the half-wing of an air gunner of the RCAF! There were two or three with first war ribbons, as well.

Officers wore metal crowns and stars on their shoulder boards. Gold shoulder cords with stars and crowns could also be attached to the shoulders. Both undress ribbons and medals could be worn, separately, of course, depending on the occasion. The Senior NCOs wore a brass RMR shoulder title on the bottom of their shoulder straps.

Scully sold the officer’s two-piece barathea patrol uniform for $80.75. Officers wore their blue forage caps, with a scarlet band ($10), complete with a gilt and silver capbadge ($3.50). Field officers, majors and above, had gold braid on the visors of their caps. The troops wore the scarlet beret ($3.25) and brass badge (60 cents), which was a ‘first,’ according to the Intercom. “We will be the only Regiment in the Militia to be granted this privilege.”

While the men wore a white belt complete with a frog for the .303 Lee Enfield bayonet, the officers wore a plum-coloured sash around their waists, with a sword ($56.25). All ranks wore white cotton gloves. The troops marched in black leather drill boots while the officers wore black leather quarter Wellington boots ($18.75 from Scully’s).

The goal, the Intercom announced, was to have the unit dressed in the new uniform for the Garrison parade on Oct. 24, 1954. “The R.M.R. will provide a splash of colour. A total of 37 units from the three armed services will be taking part in the parade and conservative estimates (say) that more than 3,000 men will turn out for it. The parade route will be from Lafontaine Park by way of Sherbrooke Street to Atwater avenue.”

The Intercom summed up by saying, “These innovations will put the Royal Montreal Regiment in a class alone in this district and will make the Unit a stand-out on ceremonial parades. Our dress will be second to none in the entire Militia.”

The RMR wore its classic patrol uniform for almost 20 years, during the golden era of the post-war militia. It was seen on the streets of Westmount at least twice a year, for the annual church parade in the spring and in November for the annual Remembrance Day parade. Then there were all the parties, dances and other social events held in the armoury. All you had to do to look smart was make sure the uniform was pressed and the buttons shined. The rest was easy.

By the early 1960s, the troops had been issued a blue forage cap, with a scarlet band, to wear with patrol dress. For their white waist belts, a rectangular brass buckle ($2.75) was worn, with the brass RMR capbadge attached to it. Now the soldiers wore two capbadges, one on top and one in the middle. They were both brass and thus had to be shined. This, in the opinion of some, was a way that the soldier could display personal pride in himself and his regiment. Others, no doubt, felt that shining boots and brass was a pain.

“Officers often had their metal rank insignia and belt buckles ‘anodized,’ plated with a mixture of gold and nickle, to avoid the need for further polishing,” said Slessor.

The last major events where the RMR wore patrol dress were held at the end of 1969. The RMR received its new Queen’s Colour – the new Canadian flag replaced the old Royal Union flag as the background for the Queen’s Colour – from Gov.-Gen. Roland Michener on Nov. 9, 1969. Because of rain, that parade was held inside the armoury instead of Westmount Park. Then the annual Remembrance Day parade was held at the Westmount cenotaph, on Sherbrooke Street. It was a splendid parade, with the brass band in attendance, complete with white Wolseley helmets. The band was not in scarlet, however, it wore blue patrols, no white belts.

During the following decades, after 1971, patrol dress was worn by many, if not most, of the RMR’s senior NCOs for their annual mess dinner. As time went on, though, the blues deteriorated. They now have proper scarlet mess kit.

Anyone interested in viewing some of these classic uniforms should pay a visit to the RMR museum, located on the west side of the armoury. Several uniforms from the mid-20th century are displayed on mannequins. The splendid mess kit uniform worn by the late Capt Vern Murray, one of the founders of the museum – it opened in 1974 – is there. He fought overseas in the war and served in the RMR from 1948-70. There is also an officers’ service dress uniform, complete with five WW2 medal ribbons.

The band wore its scarlet uniform for the 50 years it existed, from 1920-70. The musicians wore a scarlet tunic and blue trousers, with quarter-inch scarlet stripe. The tunics featured white, embroidered lace bearing a red crown every couple of inches. Tasseled shoulder cords were also worn by the musicians. A white waist belt was worn, as well as a white crossbelt. Wings were worn on the tops of both shoulders, to indicate the wearer was in the band. The picture was completed with a white Wolseley helmet with the RMR badge attached to the front.

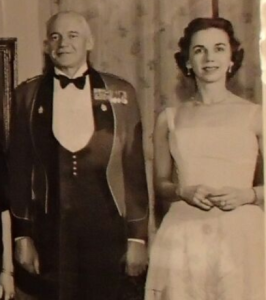

During the early 1950s, a splendid group photo was taken of the band and three high ranking RMR officers. The three were dressed in the blue patrol uniform with undress medal ribbons. The commanding officer, LCol JPC Macpherson, was there sitting in the front row, along with the adjutant (a captain) and the deputy CO, Maj CJ Pratt. Macpherson, who had won the Military Cross during the second war while serving with the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa, commanded the RMR from 1951-54. He was succeeded by Pratt, who was CO from 1954-57.

The director of music wore the officer’s version of scarlet full dress. This included gold shoulder cords and gold bullion piping on the top edge of the tunic collar. The bottom of both sleeves featured an Austrian knot. The drum major wore the very impressive baldric over his left shoulder. It featured the RMR badge, city of Westmount coat of arms and the RMR’s battle honours, all in silver and gold bullion. He also had his mace. The bass drummer wore a lion skin over his chest. This symbolizes all the campaigns the British army fought in Africa during the 19th century.

Did the RMR wear its scarlet, full dress uniforms after the war? Apparently this impressive uniform was issued and worn in the 1930s, but was put away for the duration in 1939. However, it seems it was worn at least once, by a guard of honour, for the celebrations that marked the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, on June 2, 1953.

DRESS REGULATIONS & CONFORMITY

It may be hard to believe now, but in the 1950s and 1960s there was a certain amount of pressure to wear the right clothes for the right occasion. People conformed because they were used to it and had been doing it all their lives. For both the Officers’ Mess and the Warrant Officers & Sergeants’ Mess, this was very important. In fact, the Sergeants’ Mess had a small booklet that explained everything a good senior NCO needed to know. Titled “Customs of the Service for the Senior Non-Commissioned Officers,” it was published in November, 1967, under the supervision of the RSM, WO1 RA Wheaton.

“Acquaint yourself with the Regimental Dress Regulations and follow them meticulously. Make sure you are neatly and properly dressed at all times, with your footwear shined, your uniform cleaned and pressed and you hair cut. Belts will not be worn in the mess except by the Orderly Sgt. When in uniform, watch chains, pens, pencils, trinkets, etc., are not to be worn so that they are visible. The manner in which you are turned out and your smartness of bearing is almost sure to show reflection in the appearance of your men.”

In other words, the booklet says, “Clothes do not make the man, but a good man enhances himself in the eyes of others by the way he is tuned out.”

Once an NCO makes it to the Sergeants’ Mess, he must know what “Regimental quiffs” exist so he can follow them. “He must abide by these and obtain any officially required articles immediately. The senior NCO should obtain: patrol dress, one dark lounge suit, one grey flannel suit and blazer and flannels. All civilian clothing should be carefully tailored. Ties are always conservative. Stripes are popular as in regimental ties. “Loud” patterns in ties and socks should be avoided. An NCO’s taste in civilian clothing can enhance or damn him as can the conditions of his hands,” the booklet stated.

THE RMR TIE AND BLUE BLAZER

For certain events, a blue blazer complete with a white shirt, grey flannel pants and black oxford shoes, could be worn, usually for informal events in the messes of the RMR. The blazer, which could be single or double breasted, often featured RMR buttons. A gold and silver bullion RMR crest, about five inches high, was sewn on the left of the blazer, below the breast. The overall picture was completed with the RMR tie, which features the RMR’s three colours.

The three colours, along with St Edward’s Crown, are described by Canada’s Chief Herald: the crown, (which has been altered over the years and is not depicted on the tie) represents service to the sovereign. The three colours displayed on the tie are described as follows: the blue tincture, Azure, is the heraldic colour for loyalty; the gold (Or) stripe signifies regal authority and maroon (Sanguine), is the colour of arterial blood and represents the regiment’s extraordinary valour on the battlefield.

This simple yet elegant outfit is still seen from time to time in the RMR’s venerable armoury for various social events. The tie and blazer crest are an obvious way of proclaiming the wearer’s service in and devotion to the RMR.

What else could the well-dressed RMR soldier, of any rank, buy from Scully’s? Well, there was a silk scarf for $6.25. There was a bow tie, made in rayon, for $1.50. A pair of cuff links complete with tie bar was $6.50. Strangely, the catalogue does not list an RMR tie. If you were a smoker, and just about everyone smoked back then, a Zippo lighter featuring the RMR’s gold-plated insignia cost $5.95. For a dollar more, you got the same Zippo lighter complete with an all chrome finish.

William Scully Ltd was founded in Toronto in 1877 and moved to Montreal in 1908. Billing itself as “The most complete regimental outfitter in the Commonwealth,” the company manufactured many of the classic uniforms and insignia worn in Canada by the navy, air force and army, for up to seven decades. Now located on Moreau Street, in Montreal’s east end, the company is in its fifth generation of family ownership. The current president is Will Scully, the great-great grandson of the original William Scully, who started the firm as a wholesale regimental outfitter, situated on Leader Lane in Toronto. He was an agent for British military manufacturers and outfitters.

In the late 19th century, the British empire at its height covered a huge part of the world map in pink and hundreds of thousands of officials and soldiers, both British and colonial, needed the elaborate insignia and uniforms due to their rank or civilian appointments. William Scully grew famous supplying all this to Canada’s military forces and civilian officials.

By the beginning of the 1970s, a lot of things had changed for the RMR and the militia. Student protest in the United States, opposition to the Vietnam war and declining interest in the military led to lower enrolment. How many young men wanted to get regular haircuts and submit to military discipline when they could do their own thing, man? Besides, the chicks were groovy! It was the dawning of the age of Aquarius!

The Liberal government cut funding and the reserves were hurting. The Sergeants’ Mess, which had boasted an average membership of 30-50 members (the unit had two bands after the war, the brass band and the bugle band), mustered 14 members in 1977. The Officers’ Mess was in worse shape, with ten, plus the padre, medical officer and the two honoraries. Three years earlier, in 1974, the RMR had 23 officers, plus the other four. By then the RMR band was long gone.

It is ironic to remember that the postwar planners had envisioned a militia of 180,000 men, in six infantry divisions! That dream didn’t last long. Another irony that few remember is that the historic role of the regular army, less than 5,000 men before the second war, was to support the militia with instructors, plus mounting the odd guard of honour at provincial legislatures and providing aid to the civil power in case of labour disturbances. It was the militia, which at its height mustered up to 75,000 men, that enjoyed social prestige and a high profile. Some saw the tiny regular army as a waste of money, comprised of men who couldn’t do any else.

In 1972, the soldiers of the RMR were issued with the new Canadian Forces service dress uniform, commonly known as ‘CF greens.’ The post-war golden era, for uniforms at least, was officially over, for better or for worse. Now everyone looked the same and wore the exact same boring, utilitarian uniform, whether you were army, air force or navy. But that will be covered in another story.

If anyone has anything to add the author would be delighted to hear from them. He would like to thank LCol (Ret) Harry Hall, Maj (Ret) James Anderson, and Capt (Ret) Hamilton Slessor for their help.