by Buzz Bourdon (late the RMR, 1975-82)

Two documents that had been buried and forgotten for over seven decades in the archives of the Department of National Defence saw the light of day recently, for the second time in eight years, giving collectors and researchers a tantalizing glimpse of a badge that never was.

In 1935, the commanding officer of the RMR, LCol Victor Whitehead, submitted a request, through military channels, for his unit to adopt the Blue Cloth Helmet, Infantry Pattern, in place of the white Wolseley helmet. The Wolseley helmet had been worn by the RMR’s brass band, complete with scarlet tunic and blue trousers, sometime after it was formed in 1920.

If the request was approved, hundreds of helmets would have to be ordered and manufactured from one of the hundreds of firms that supplied the military units of the far-flung British empire. A large-scale helmet plate that proclaimed the title of the RMR would also have to be designed and made. This new helmet plate would be worn on the front of the helmet.

First authorized by the British army in May, 1878, the Blue Cloth Helmet, also known as the Home Service Helmet, was made of cork and lined with blue cloth. It featured a spike on top, which was inspired by the Prussian army, and had a curb chain secured by a rosette on either side. Certain branches of the army replaced the spike with the “ball in leaf” device.

This helmet was the headdress worn by infantry regiments, except highland, fusiliers, Guards and rifles, with the full dress uniform, until the start of the First World War. After 1918, full dress was not often seen in Canada and Britain.

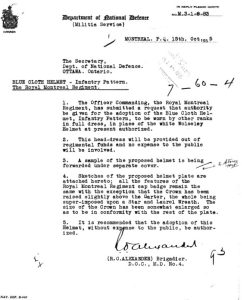

The district officer commanding Military District No. 4, BGen RO Alexander, was happy enough to approve the RMR’s request in a letter dated Oct. 15, 1935, addressed to the Secretary of the Department of National Defence, in Ottawa.

The request also included a sketch of the proposed helmet plate, prepared by JR Gaunt & Son Ltd., “medallists and badge makers.” Originally established in Birmingham, England, in the mid-19th century. Gaunt opened a branch in Montreal sometime after 1900 and supplied badges and insignia to Canada’s military forces. The firm was particularly known for its exquisite gilt and silver officers’ capbadges. The Montreal branch closed circa 1983. The English firm resumed trading in 2010.

The sketch of the plate shows the usual design: a very large, eight-pointed star with the Tudor, or King’s, Crown at the top. Inside the plate, a maple leaf bears the unit’s title: ROYAL/MONTREAL/REG. The maple leaf is surrounded by the garter and motto, and a wreath of laurels. ‘CANADA’ is shown at the bottom.

Helmet plates are much larger than the modern cap badge worn on forage caps, and later berets, since the end of the 19th century. They are a good five inches across, and about eight inches high. Made of brass for other ranks, the officer versions are gilt, often with silver and enamel added.

Whoever designed the helmet plate for Gaunt did not have to use a lot of imagination: all he had to do was include the central part of the RMR cap badge in the middle of the plate. That means the maple leaf and the unit’s title was copied from one to the other.

Since the RMR’s request was made in the middle of the great depression, Whitehead was careful to emphasize that the helmets would be provided from regimental funds. In other words, no public money would be spent.

Unfortunately, no reply to the DOC’s request on behalf of the RMR seems to have survived. It is likely that the RMR either never got official approval for the blue cloth helmet and its plates, or, if it did get approval, could not raise the funds to buy them.

Even at 1935 prices, buying 200-300 helmets, complete with helmet plates, would have been prohibitively expensive for any militia unit of that era, unless of course it had a rich honourary colonel happy to write a cheque. It certainly would have cost several thousand dollars, in an era when government funds for training were almost non-existent and officers donated their army pay to the unit fund.

Or maybe someone decided that the white Wolseley helmet was perfectly good enough for the RMR, since the band already wore it. It was worn with a brass RMR capbadge secured on the front.

Where did the documents come from? In 2006, Capt Grant Furholter, who at the time was regimental sergeant-major of the RMR, was conducting research into the history of the RMR and how that related to the 58thWestmount Rifles.

Founded in October, 1914, two months after the RMR, the Rifles were inactive in 1920 and waiting to see what would become of them. Discussions had started earlier, in 1919, with high-ranking officers of the war-time 14thBattalion, usually called the RMR, about a possible amalgamation. Those discussions were eventually successful and the Westmount Rifles and the RMR amalgamated in 1920.

Furholter got in touch with an RMR officer, LCol Brian Sutherland, a long-time staff officer in Ottawa who originally joined the RMR in 1969. Sutherland did some research and the two documents eventually surfaced from the tons and tons of paperwork stored deep in the national capital in various archives.

Now, we have the story of the helmet plate that never was. It is unlikely a prototype was ever made but at least we have the sketch displaying what might have been.